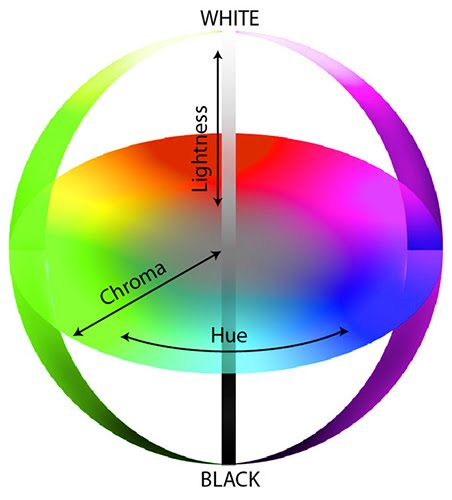

Inkjet printing in color can be done with only three inks: cyan (C), magenta (M) and yellow (Y). In principle, this is all that is needed to reproduce the colors accessible to humans. In our eyes we have rods, that see only the monochrome, and three different kinds of cones, that differ in spectral sensitivity. The cones enable us to see the world in color. As the number of the cone types is three, the perception of human color is normally three-dimensional, that is three parameters are needed to describe it. A common selection of parameters is lightness (L*), chroma (C*) and Hue (H*). Hue stands for the shade of color, Chroma, for the inensity of color, and lightness for the overall lightness/darkness of the color. The L* of 100 corresponds to white, whereas low L* values in the range of 2-10 corresponds to blacks. As the black is the primary focus of this post, we will be mostly talking about L*.

Note that some people are born with only one or two kinds of cones; for those people, the color space is two-or even one-dimensional. This effect is known as color blindness or daltonism.

By blending cyan and magenta ink dots, we can produce different shades of blue. Cyan and yellow will produce different shades of green, and magenta and yellow will produce different shades of red. Finally, by blending cyan, magenta, and yellow dots one can produce different shades of gray and black, which transition into CMYRGB colors. Thus, by manipulating the number of cyan, magenta and yellow dots one in principle can reproduce the whole color palette of human vision.

Why then the high end printers have so many inks? Thus, a photo printer often has light cyan, light magenta inks, as well as gray inks, in addition to CMY. Nearly all printers have a black ink (K) in addition to CMY. Some industrial printers are hexachrome systems CMYRGB and utilize red, green and blue inks in addition to cyan, magenta and yellow. Finally, many printers utilize spot colors, such as metallic and fluorescent/phosphorescent. Each of those inks serves a certain purpose, as described below.

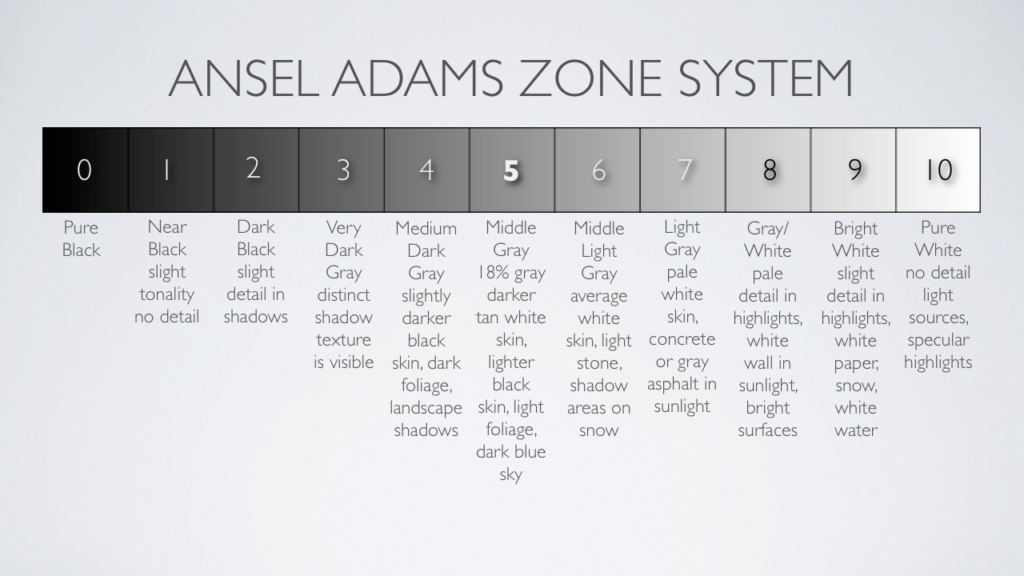

- Black inks. Although blending cyan, magenta and yellow dots does produce black, it is rather a very dark gray, not black, with L* as high as 20. For a high quality imaging, a dedicated dark black is needed as it increases the dynamic range of imaging, and reduces the accessible L* to the value of 2-5. The concept was popularized by the great American photographer, Ansel Adams in application to Black-and -White photography, as eleven zones of gray that are required in high quality B/W photo imaging: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zone_System. Zone 10 coresponds to White; Zone 0 corresponds to black.

Figure 3. Ansel Adams’ Zone System

Without dedicated black inks, reaching Zone 0 would not be possible and the image would be truncated, say, at Zone 3.

The use of black inks in printing (that is, CMYK ink set) has a long history and goes long before the digital printing times, and Ansel Adams 11 Zone system. Commercial offset printers were CMYK type for a long time.

For inkjet specifically, the black ink is often carbon black pigment based as it is used for the text and graphics. Having black pigment helps with the quality of the text and line art as it reduces ink wicking along the fibers of paper.

The black ink is also very much needed for the photo printing as described above. If the printer is used on glossy paper in combination with dye-based inks, the true photo black ink also needs to be dye-based, otherwise some gloss nonuniformity will be produced. However, for digital fine art papers (DFAs), pigmented black is preferred as it creates a darker black. As a result, some high-end inkjet printers contain two different black inks, one for glossy media and one for DFA.

Figure 4. 10-ink system for a Canon pigmented printer includes two blacks: a ‘glossy’ photo black (PBK) and a matte black (MBK) which produces low L* values on DFA media.