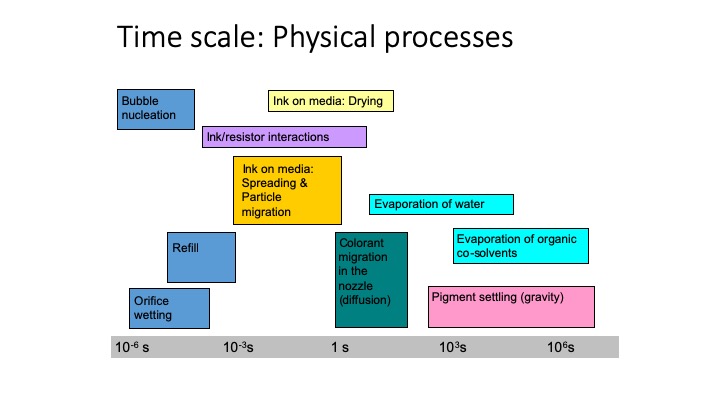

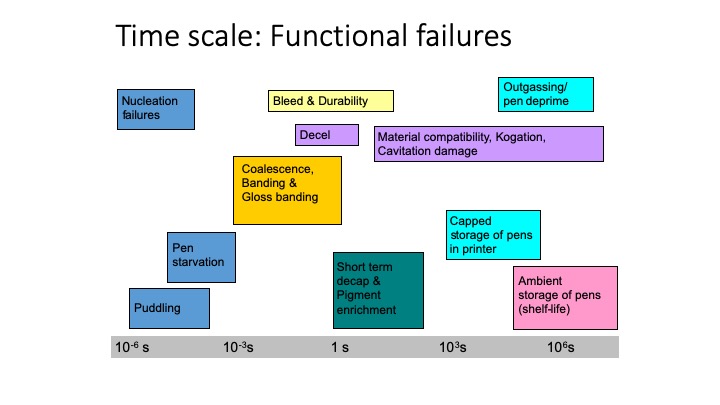

There are many physical processes in inkjet can could lead to functional failures, as shown in Figures below.

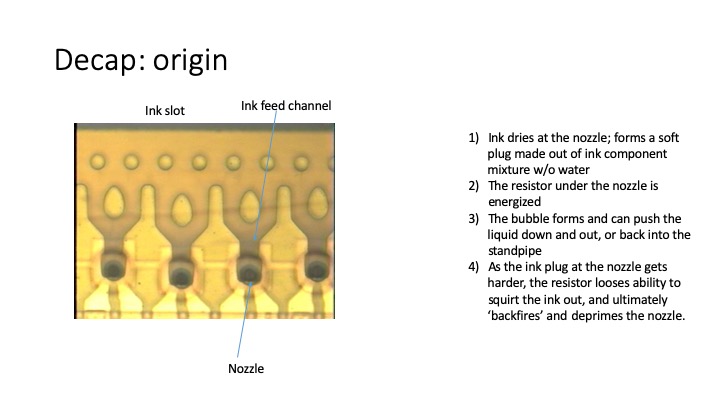

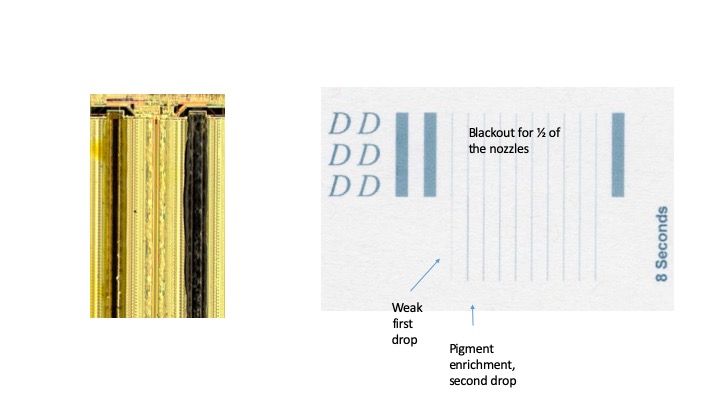

Inkjet nozzles loose water by evaporation on-the-fly very quickly, at the rate of several nanograms per second. This may not sound to be much, however, if one keeps in mind that an inkjet drop is only few nanograms in size, it becomes significant! As a result, if the nozzle stays idle for a few seconds, it may have a difficulty to print again. To complicate the matter, nozzles do not print all the time; in fact, nozzle usage is image and printhead location dependent. As a result, all the printheads need to spit the inks on a constant basis, to constantly bring up all the nozzles to the ‘fresh’ state. A sizable fraction of ink is therefore waisted in printer spittoons. This phenomenon of loss or misdirection of a nozzle after a short wait time is known as the short time decap.

It is desirable to have a working inkjet nozzle for at least, a few seconds. This time is determined the time needed to travel from the spittoon to the printing location, and therefore depends on by the scanning speed of the printhead and the width of the print bed. In other words, the printhead as it comes from the spittoon or from a capping station, to the area it needs to print, should have the nozzles in a state of a ‘good health’.

The discussion above covered the case of scanning printheads. If the printhead does not scan over the paper but stays immobile, spitting on-the-flight cannot be easily implemented— this arrangement is often seen in large printing presses that utilize Page-Wide Arrays (PWAs). In this case, for the sheet fed printers, spitting is done between the sheets of paper. For a web press that prints on a continuous roll of paper, the only way to spit the inks is on the web, either as a highly distributed ‘random noise’, or in the locations of no importance that will be cut in the following finishing process.